50 Great Canadian Films Worth Checking Out

In honor of National Canadian Film Day, I have taken it upon myself to create a master list of essential Canadian films, from the beginning of the 20th century up until the present day. While there are quite a lot of major actors and directors to come from the Great White North, there are hundreds of titles which seem to not get much exposure outside of the confines of the country. With these selections, a few of which are available to watch online (through the graciousness of the National Film Board), I'm hoping to provide some great recommendations for famed, important titles that are in need of more attention.

Back to God’s Country (1919)

For this list, it made sense to start as far back as possible, and David Hartford’s silent film Back to God’s Country is the perfect place to do so. The earliest surviving feature film in Canadian cinema, it was also the most successful silent film of its era, not to mention the earliest example of a Canadian feature authored by a woman (Nell Shipman). Shipman plays the lead role of Dolores, living peacefully in the woodlands amongst a bevy of animals with her husband. One day, a villainous Mountie captures the both of them, and only through her cunning and wit can the day be saved (of course, she is assisted by her forest dwelling friends). Thought to be lost for many years, a print of Back to God’s Country was discovered in Europe during the 1980s, restored, and now can be preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Rhapsody in Two Languages (1934)

Gordon Sparling’s short documentary is set over a 24 hour period in Montreal, squaring in on the division between the country’s most bilingual city (as the film’s announcer states, “It’s French, It’s English, It’s Montreal!). Akin to city symphony montage films like Dziga Vertov’s The Man With a Movie Camera, a rhythmic assembly of various citizens going about the monotony of their lives is sprawled out, eventually climaxing in an exciting, frantic display of fun and good times.

Churchill’s Island (1941)

A propagandistic assembly of newsreel footage, Stuart Legg’s short played throughout World War II in cinemas, depicting efforts on the homefront and their impact towards the British and Canadian forces fighting overseas. The film is especially notable for being the first recipient of the Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject, and the first to be awarded to the National Film Board of Canada as well.

Begone Dull Care (1949)

Norman McLaren, a pioneer in animation through his approach to utilizing a myriad of experimental techniques, made his first of many integral works, with this cacophony of visual and audible manipulation, set to the music of a young Oscar Peterson. Instilling a range of techniques on the film itself, frame by frame, it’s certainly one of the most unique and treasured shorts, and one that certainly carries his unique stamp.

La petite Aurore, l’enfant martyre (1952)

Jean-Yves Bigras was one of the very first French-Canadians to assume a position at the NFB, though his greatest achievement came from this title. The true story of a young girl, Aurore, living in a rural village with her dying mother, who is placed in the care of a cruel, sociopathic neighbor who subjects her to a great deal of abuse. Controversial upon release given the notoriety of the events themselves and Aurore’s own father attempting to prevent the film from being seen by audiences, it remains a classic staple of Quebecois cinema.

Neighbours (1952)

Possibly the most well-known film made by Norman McLaren, Neighbours fuses together live-action actors with stop-motion photography, in a scenario between two rivals attempting to ensure proper ownership of a single flower growing between their lawns. Inspired by McLaren’s journey to China during the Korean War, it was initially not well-received by Canadian audiences, with several exhibitors not interested in showing it. However, once the film received an Academy Award, the second for an NFB production, its notoriety spread like wildfire, granting it a level of acclaim and exposure unlike any other Canadian short has ever seen.

Tit-Coq (1953)

A story of love and life at wartime, Tit-Coq tells the story of a man looking for his sense of purpose, having grown up with the sense of not fitting in anywhere. It’s through the love of a woman, Marie-Ange, that Tit-Coq begins to feel a sense of belonging, one he must strive and fight to uphold after he is called overseas to fight in WWII and the object of his affection is swayed into marrying another man. A beloved classic of Quebecois cinema.

Corral (1954)

Set amidst the plains of Alberta, Colin Low’s short documentary follows the process of ‘breaking a horse’, as we follow one cowboy tame what once ran wild. Though it only runs a bit over 10 minutes, the film is notable for how it seeks to upend the traditional depiction of the cowboy in American film and television of the then-contemporary period, choosing to showcase one extended process with no exposition. Corral would go on to win the Best Documentary Award at the Venice Film Festival, a major achievement for the NFB.

La lutte (1961)

A project developed and executed by several pre-eminent Montreal directors (Michel Brault, Claude Jutra, Marcel Carriere, Claude Fournier), La lutte was originally intended to highlight the fake qualities of wrestling, before the filmmakers decided to take the opposite approach and focus on the inherent beauty of the practice instead. What results is a fascinating, enthralling look at the feats of strength – physical and emotional, that go into the sport, that there’s much more to it than what is perceived on the surface.

Lonely Boy (1962)

Roman Kroitor and Wolf Koening follow teen sensation Paul Anka on tour, as he serenades fans while struggling to keep up with the public demand for his personality. A revealing look at the side of fame that had not been often focused on, much less with an actual entertainer, Lonely Boy is a truly moving work and more than anything, shows that fame and popularity have their drawbacks. The film won the Canadian Film Award for top film of the year, and was nominated at the BAFTAs for best short film – today it serves as a foreboding message to the modern generation’s bevvy of pop stars.

21-87 (1963)

An experimental collage film from Arthur Lipsett, made from the remnants of other works done for the NFB as well as Lipsett’s own created footage shot in urban settings, The film itself is a wonder to behold, and it also has the added ability of being a huge inspiration on filmmaker George Lucas, who repeatedly referenced the four digit title in Star Wars as a tribute.

Pour la suite du monde (1963)

A surreal blending of fact and fiction, set within a remote community where fishing for beluga whales is a long-dormant custom, this feature from Michel Brault, Marcel Carriere, and Pierre Perrault is a fascinating expose on the ways in which narrative can be altered or construed to generate a more resounding effect on the images and moments that are captured. Featured in the 1963 Cannes Film Festival and ranked among the Top 10 Canadian Films of All Time (1984 edition) by TIFF, it remains one of the most intriguing works in the docufiction canon.

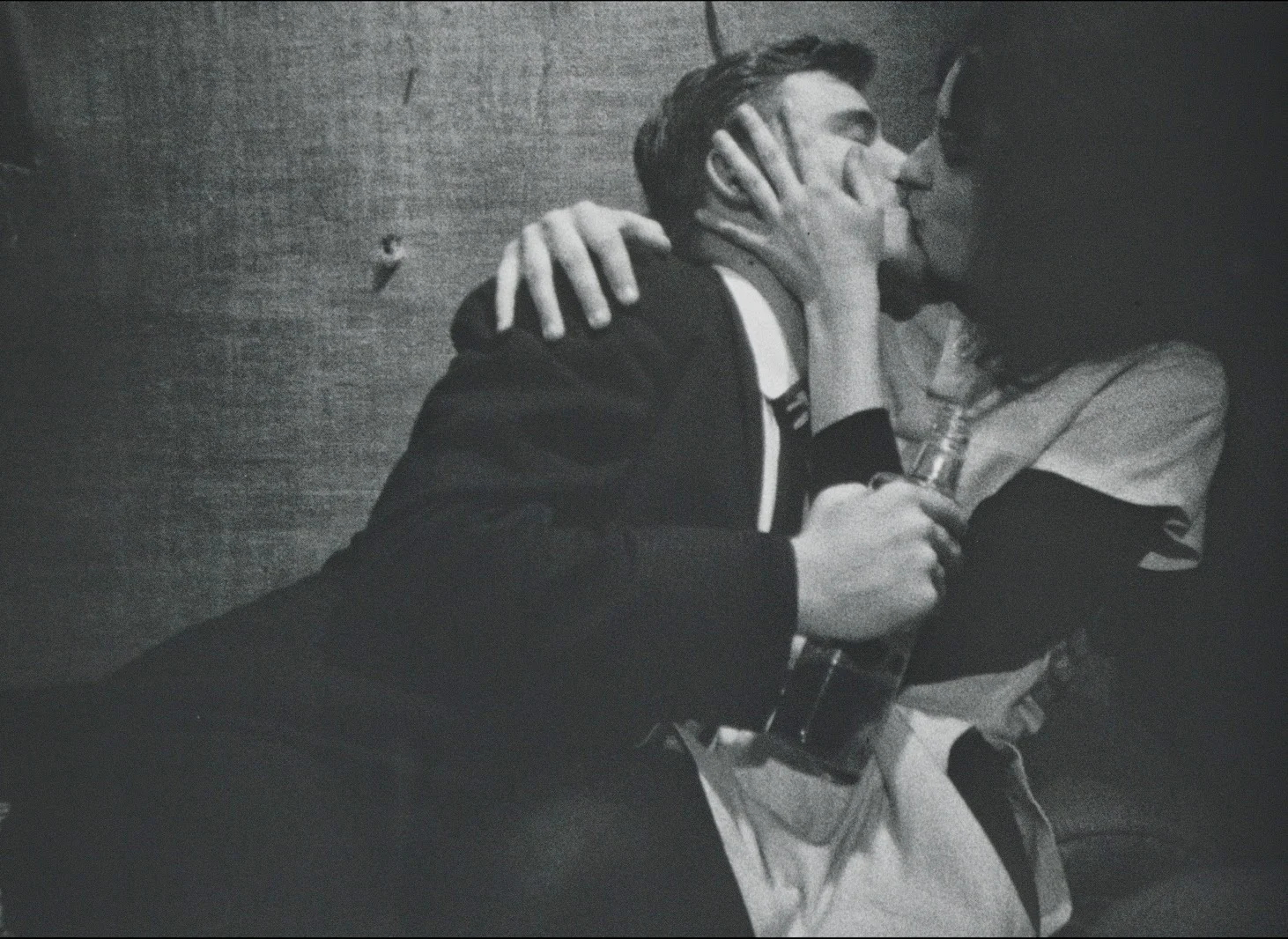

The Bitter Ash (1963)

Low in budget but high in its aims, this slice of life emerging out of the 1960s countercultural movement is a direct commentary on the faults of the past era and the hope for the future, one achieved through rebellion of the youth generation and their hardships. Set in Vancouver, it follows a group of adults attempting to make a life for themselves, relinquishing the rules and customs of the past generation, but finding immense struggle from the same place. Director Larry Kent’s first feature, and one that showed he had immense talent right out of the gate.

A tout prendre (1964)

Claude Jutra’s first film not created through the NFB is a highly personal affair, taken right from his own life in playing himself as a man fighting to accept his homosexuality, amidst a changing landscape fraught with scrutiny and external pressures. A tout prendre would go on to win Best Film at the Canadian Film Awards and be seen as a breakthrough for LGBTQ cinema in the country. In a cruel twist of life imitating art, the film’s finale, in which Jutra’s on-screen essence commits suicide by drowning in the St. Lawrence River, would occur for real over 20 years later after Jutra was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

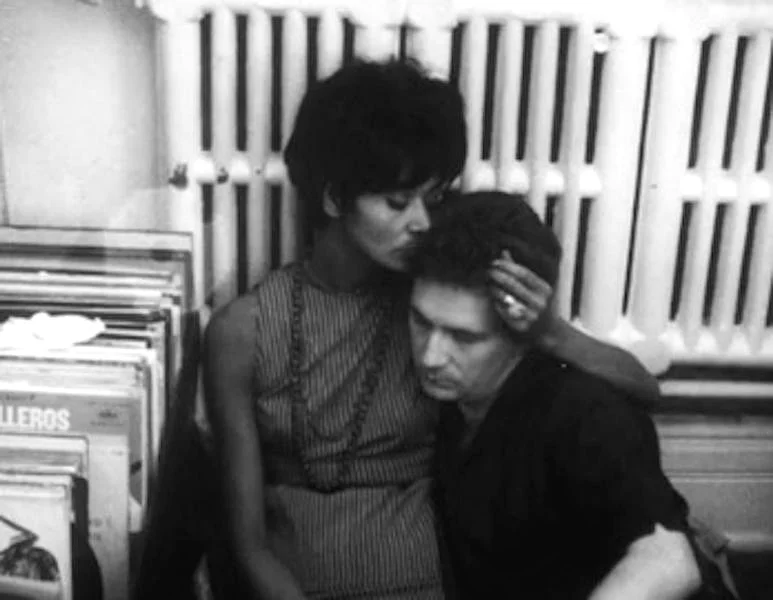

Le Chat dans le sac (1964)

A microcosmic narrative in which the role of Quebec in Canada’s larger construct is relayed through the experiences of a young man, Gilles Groulx’s feature has been repeatedly mentioned as an instrumental piece of work in Quebecois cinema and its burgeoning essence. For a province that had long been under the thumb of religious thought and government control, it was a wakeup call to the potentials and possibilities for starting anew, as framed by its stylings of the French New Wave by directors like Jean-Luc Godard.

Nobody Waved Good-bye (1964)

Don Owen’s tense story of young love and the struggles which abound from trying to make it alone, Nobody Waved Good-bye has been cited as the Canadian response to other youth-in-dilemma films like Rebel Without a Cause and the countercultural classic Midnight Cowboy. We follow 18-year-old Peter, who rebels against his parents’ values and finds companionship with his girlfriend, Julie. A series of events leads him to running away from home and attempting to live on his own terms, but soon finds that he doesn’t have what it takes to survive the way he thought. Stark in its depiction of a hopeless future for its protagonist, Nobody Waved Good-bye is among the great Canadian independent features, and one which has managed to stand the test of time as well.

The Things I Cannot Change (1967)

Running at just under an hour but densely packed with fraught emotion and adversity, Tanya Ballantyne’s documentary looks at the life of the Bailey family, living in destitute conditions in Montreal and struggling to get by with little money and food against the odds. The first film in the NFB’s Challenge for Change program, it provided a snapshot into the lives of the families across the country who went largely unnoticed by the system, struggling to survive and keep moving forward with the resolve that things will get better.

Warrendale (1967)

Considered to be one of the most important and treasured directors in the documentary tradition, Allan King’s first feature-length documentary is set in a Toronto mental hospital for emotionally disturbed children, over the course of a month and a half. Hard to watch at times as many children are physically restrained in bouts of severe anger, the film was famously banned from being shown on CBC due to the profanity which King refused to censor, though it would later end up being honored as Best Film at the Canadian Film Awards.

Wavelength (1967)

Michael Snow’s experimental masterwork is certainly a divisive affair. Running at 42 minutes, it comprises a slow long zoom towards a window in a small apartment building, shot over the course of a week as an assemblage of editing techniques and transitions are placed throughout, granting a transient experience to unfold that shifts the boundaries of what’s possible in the span of a movement. While frustrating for sure, it beckons the viewer to look closer, beyond the surface of the image itself, to uncover something more meaningful – as it is one of the most literal concepts of a ‘motion picture’ in cinematic history.

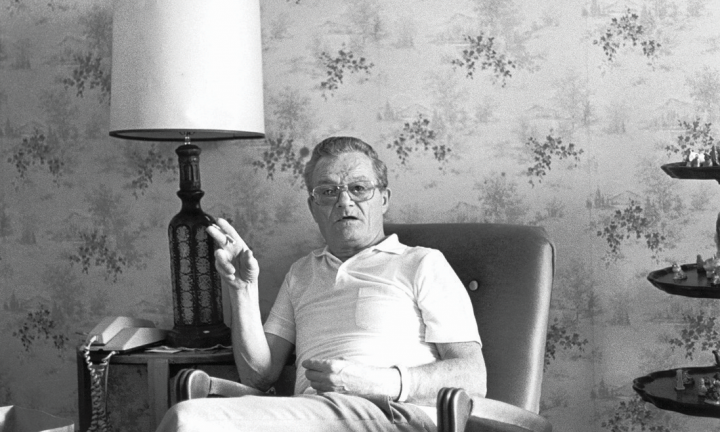

A Married Couple (1969)

An ‘actuality drama’ that centers around a couple desperate to save their marriage amidst a changing time period, Allan King’s documentary follows the life of Billy and Antoinette over ten weeks, two people who don’t seem to be in love anymore, as seen through the constant bickering and verbal assault that emerges between them, and the happiness that only shines through in quieter moments. The implementation of the camera in their daily lives as a curative tool, and the couple’s willingness to document their lives on screen without holding back, make it a crucial, moving work of non-fiction cinema.

Goin’ Down The Road (1970)

Two friends travelling from Nova Scotia to Toronto in search of a better life makes for a unique look at the country’s most populous city as it entered a new decade. Donald Shebib’s Goin’ Down The Road has been cited as arguably the most Canadian movie ever made, it undertakes a road narrative in the same vein as Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider, moving from place to place, vocation to vocation, getting a sense of the surrounding environment and passing through while learning a series of harsh lessons at the same time.

Mon oncle Antoine (1971)

Claude Jutra’s coming of age story set around Christmas in a desolate Quebec mining town in 1949 is one that provides a range of beautiful and painful moments. Another film which has been thought by many to be the best Canadian film of all time, with a rich, lush atmosphere that regales in the sense of coldness that occupies most of its environment, it follows Benoit (Jacques Gagnon) as he spends time with uncle Antoine (Jean Duceppe) who runs the town general store (and undertaker business). In a short span of time, Benoit gains a newfound appreciation for life, in all its wonders, as finite as they may be.

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz (1974)

A young Jewish man in the end of the 1940s (Richard Dreyfuss) undertakes a quest to become powerful and successful in order to appease his father, in this slice of life from Ted Kotcheff (written by famed Canadian author Mordecai Richler). Made right after Dreyfuss gained fame for American Graffiti (and prior to his work in Jaws), it makes for an engaging look at Canada’s post-war period, full of people striving to accomplish more and rise above the ranks to success.

Black Christmas (1974)

This film from Bob Clark (A Christmas Story) is distinguished for being one of the very first slasher films in the horror genre, predating John Carpenter’s own seasonal favorite Halloween by four years. Set around a university campus during the holidays, a group of sorority sisters are mercilessly stalked by an unknown and deranged perpetrator. Inspired by Italian horror and the giallo subgenre, it contains many of the traditional conventions of modern horror films, such as the ‘final girl’ who must vanquish the forces of evil after there is no one left, and the idea of a masked, shadowy figure who’s identity isn’t revealed until the final scene.

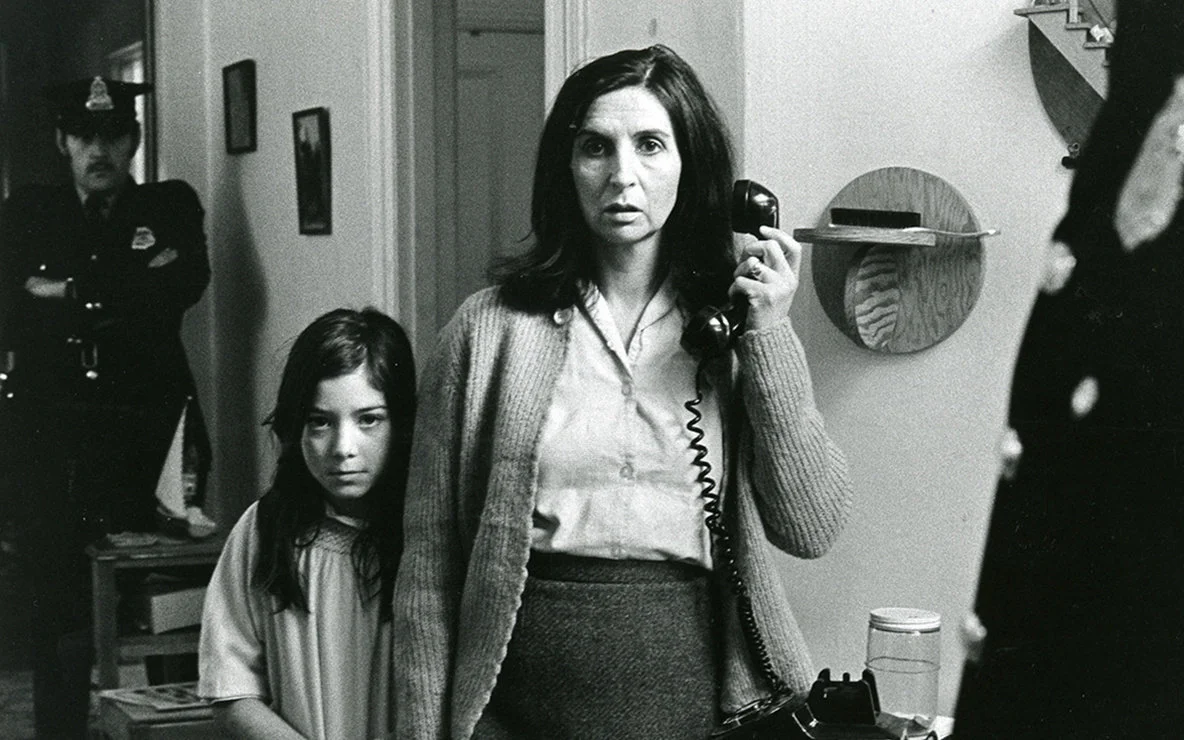

Les ordres (1974)

Innocent citizens are taken into custody during Quebec’s Black October crisis, in this docudrama from Michel Brault. Following the 1970 War Measures Act which enabled police to arrest anyone suspected of terrorist activities without evidence or charges, the film looks at five people giving their personal accounts into the event. A shocking, brutalistic endeavor that shows what happens when certain rights and freedoms are ignored for the guise of security, it would share a prize at Cannes for Best Director (alongside Costas-Gravas’s Section speciale).

Shivers (1975)

David Cronenberg’s first feature film is set within a Montreal apartment complex that undergoes an epidemic via a body parasite which infects various inhabitants. Setting the stage for his later works to come, that would take different approaches to body horror in their own ways, Shivers can be seen as his most optimistic film, once the widespread infection reaches its zenith and begins to spread outward beyond the complex – signaling a change in social norms and customs against those of the past. Highly controversial upon release and the subject of many news stories who were angered that the film was partially funded through Canadian tax payers’ money, it nevertheless marked the emergence of a new, important voice in horror cinema.

J.A. Martin, Photographe (1977)

A photographer and his wife embark on a cross-province journey together throughout Quebec, in an attempt to find a spark in their marriage that has lost some of its vitality. The most famous film from director Jean Beaudin, and the winner of several international prizes and awards (including a Best Actress win at Cannes for Monique Mercure), it is ripe with lush, exquisite cinematography and carefully crafted mise en scene.

The Silent Partner (1978)

Darryl Duke’s suspense-thriller shot and set in Toronto is one of the trademark films of the Canadian tax shelter era. Starring Elliott Gould (who earlier on in the 1970s was a very bankable star but eventually lost audience interest in Hollywood pictures) as a bank teller caught up in dangerous game of cat-and-mouse with a thief (Christopher Plummer) attempting to make off with a large sum of cash from his institution. While many titles of the tax shelter era were made for the purposes of producers getting government money to shoot a film and then never hit multiplexes, The Silent Partner is one of the more prominent examples of a film that managed to become a somewhat popular feature, enough to the point where it has been released and made widely available on home video.

Meatballs (1979)

A box office sensation, Ivan Reitman’s camp comedy is admittedly not a great film, but important nonetheless. It helped launch Bill Murray’s career in film, as well as Reitman’s, and it’s unsure if the two would have been able to make Ghostbusters without it. Made for less than $2 million dollars and grossing over 20 times that amount, it held the record for the biggest Canadian film until Porky’s would come along just a few years later.

Les Bons debarras (1980)

Another dark classic of Canadian cinema, Les Bons debarras is about a young girl, her mother, and her mentally challenged uncle living in the Quebec Laurentians. A strained relationship between the three comes into play, and what emerges is a destructive play of power and manipulation, the life that can be versus the one is, ending ultimately in tragic form. At the time, it was the most popular Quebecois film since Mon oncle Antoine, and gained an overwhelming amount of recognition and praise, both within and outside of Canada.

Heavy Metal (1981)

An animated cult classic inspired by the fantasy comic magazine of the same name, Heavy Metal is an anthology film of various stories, all connected through a glowing orb known as the Loc-Nar, or ‘the sum of all evils’. What entails is a broad range of science fiction and mystic stories, moving through different dimensional planes and eras, making for a feature that’s greater than the sum of its parts. While certainly some parts haven’t aged well, it makes for fun escapism with a great soundtrack to boot.

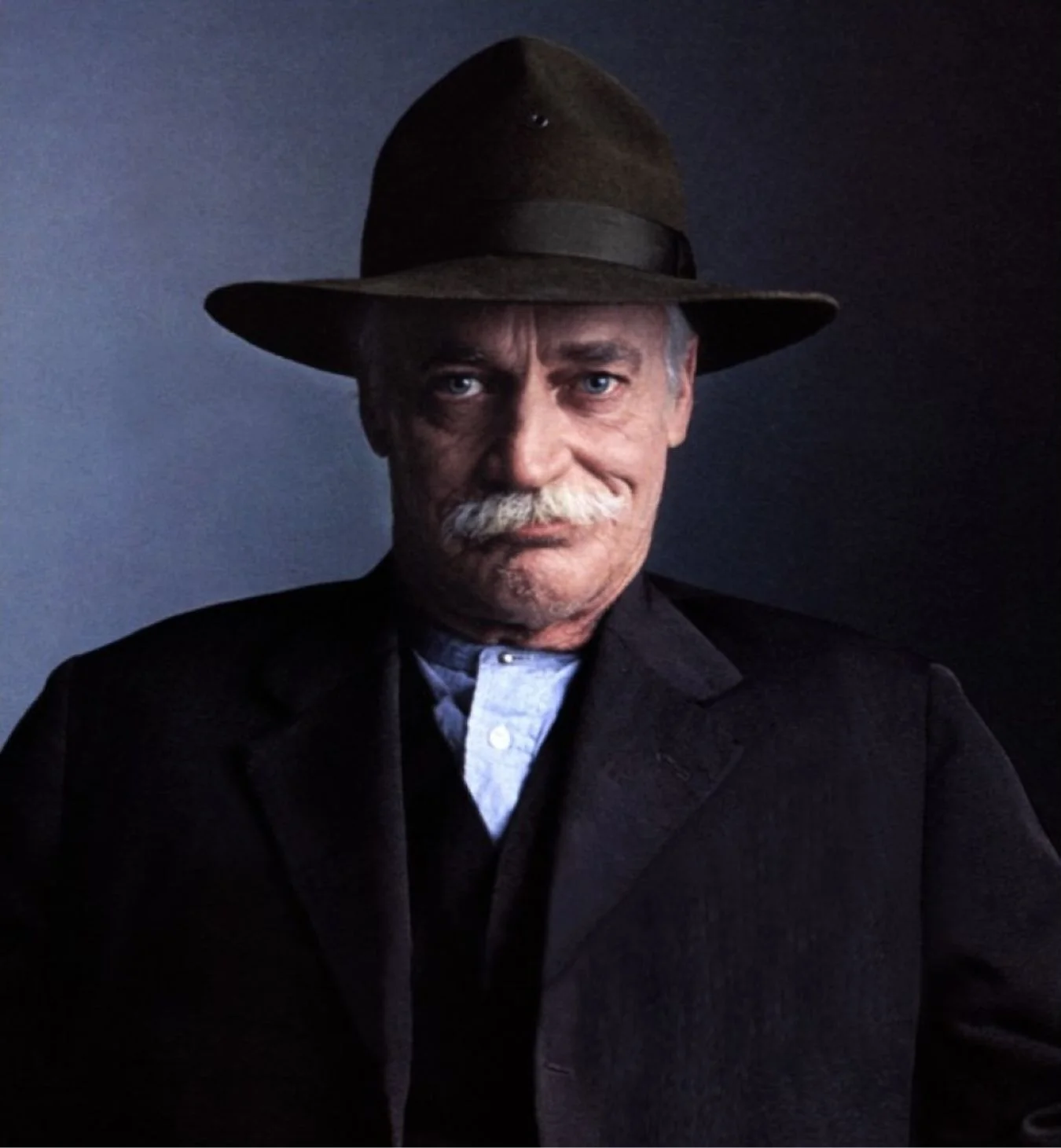

The Grey Fox (1982)

An adventurous Western biopic on the life of Bill Miner (Richard Farnsworth), known as ‘The Gentleman Bandit’ and famous for executing the first Canadian train robbery at the start of the 20th century, The Grey Fox has been honored as one of the most important Canadian films in history. Sadly, it has never been made available on DVD (officially), though one hopes such a fate will change soon enough.

Videodrome (1983)

Max Renn (James Woods), owner of a Toronto TV station specializing in sleaze, happens upon a pirate satellite transmission broadcasting a program called ‘Videodrome’ that opens up a whole world of innate desire and freakish consequences. Easily among David Cronenberg’s greatest works, Videodrome has held a firm spot within the canon of 1980s sci-fi/thrillers, most evidently from its concept that is adequately realized through the broad range of practical effects work on display.

Crime Wave (1985)

Crime Wave, directed by John Paizs, is the story of Kim, a young Winnipeg girl who befriends her quiet introverted neighbour Steven Penney, a troubled screenwriter who is only able to construct beginnings and endings to stories, but not the stuff in-between. Kim assists Steven in making ‘the best colour-crime movie there is’, by helping him write the middle section of ‘Crime Wave’, his dream project. What entails can only be described as a pulpy comedy in a meta-fictional framework that encases multiple stories within itself, as the story undergoes many surprising twists and turns. Paizs utilizes a broad range of visual style, taking on a campy aesthetic straight from educational films and B-movies of the 1950s. He appropriates many facets of American culture into the narrative, and in doing so speaks to the position of lack that many Canadians feel when attempting to carve out and uphold a distinct artistic identity.

The Decline of the American Empire (1986)

Four History professors living in Montreal gather for a weekend cottage retreat with their better halves in Denys Arcand’s intellectual take on The Big Chill. It’s a satirical exploration at changing attitudes of the time with regards to sex, gender, and relationships, and while its central characters can be a little too much to handle, it helps to drive the inevitable clash that emerges in the film’s finale.

I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing (1987)

Patricia Rozema’s feature debut is a charming foray into the life of Polly (Sheila McCarthy), who in her thirties lands her first real job as the secretary for an art curator, as she navigates the world around her that’s full of fantasy, and later, falling in love with another woman. It’s a film that harbors around the idea of one’s own innate desires and attempting to project them into actuality, while also making sly commentary on the ostentatious sense of artificiality within the visual art world, and the loveliness that can emerge out of simplicity, unaffected moments.

Dead Ringers (1988)

British actor Jeremy Irons does double duty in David Cronenberg’s story about twin gynecologists, Beverly and Elliot Mantle, so attached to being with one another that their trickery extends into their work and personal lives. The primary story itself is quite ominous, with two people sharing one idea of self, but the later breakdown that emerges from the failure of the twin’s exploits becomes depressing on a whole other level. Full of the weird, provoking imagery one expects from a Cronenberg film but with a more grounded sense of characterization, it’s not hard to see why Dead Ringers is his most accessible and praised film.

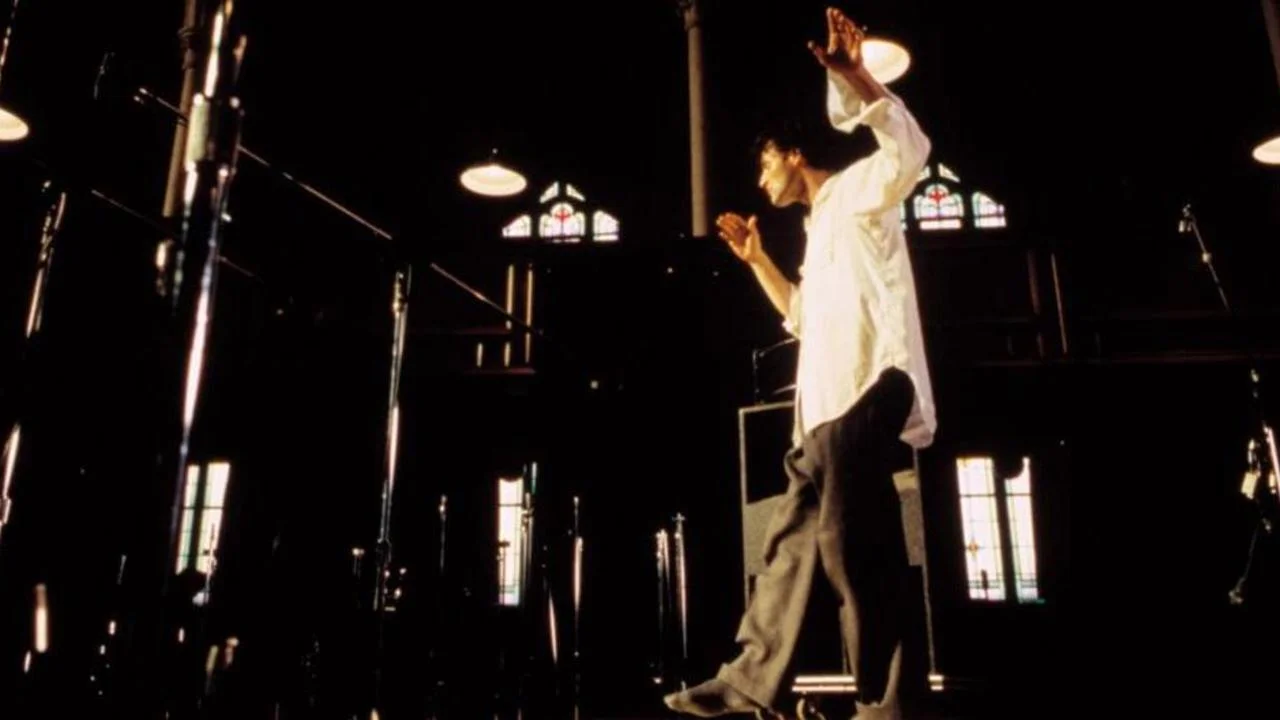

Jesus of Montreal (1989)

An assessment of religious obstruction against changing values, Denys Arcand’s remarkable followup to The Decline of the American Empire focuses around a group of actors putting on a re-imagining of the Passion Play, which gains the unwanted attention of the Catholic Church. At the same time, various members of the group begin to experience changes in their lives which mirror the Play itself. More than anything, it’s a film driven by the essence of spirituality and how to apply the lessons of the past into our contemporary lives, and another major achievement for Arcand.

Leolo (1992)

A young boy develops a fantasy world to come to terms with the real mental illness which plague his family life in Jean-Claude Lanzon’s whimsical feature. Not quite light-hearted, as it is packed with sad moments, but the surreal qualities of the story itself and the visual splendor that emerges make for a complex, engaging, and overall fascinating take on the typical bildungsroman tale.

Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould (1993)

A series of vignettes covering the life of the famed Canadian composer (played by Colm Feore), that defies simple categorization. Not merely a biopic or even a tribute, it uses each brief section to say something about it’s titular focus in a new, inspired way, giving the viewer a multifaceted take on an enigmatic figure. A masterpiece to say the least, and one that feels just as fresh nearly 25 years later.

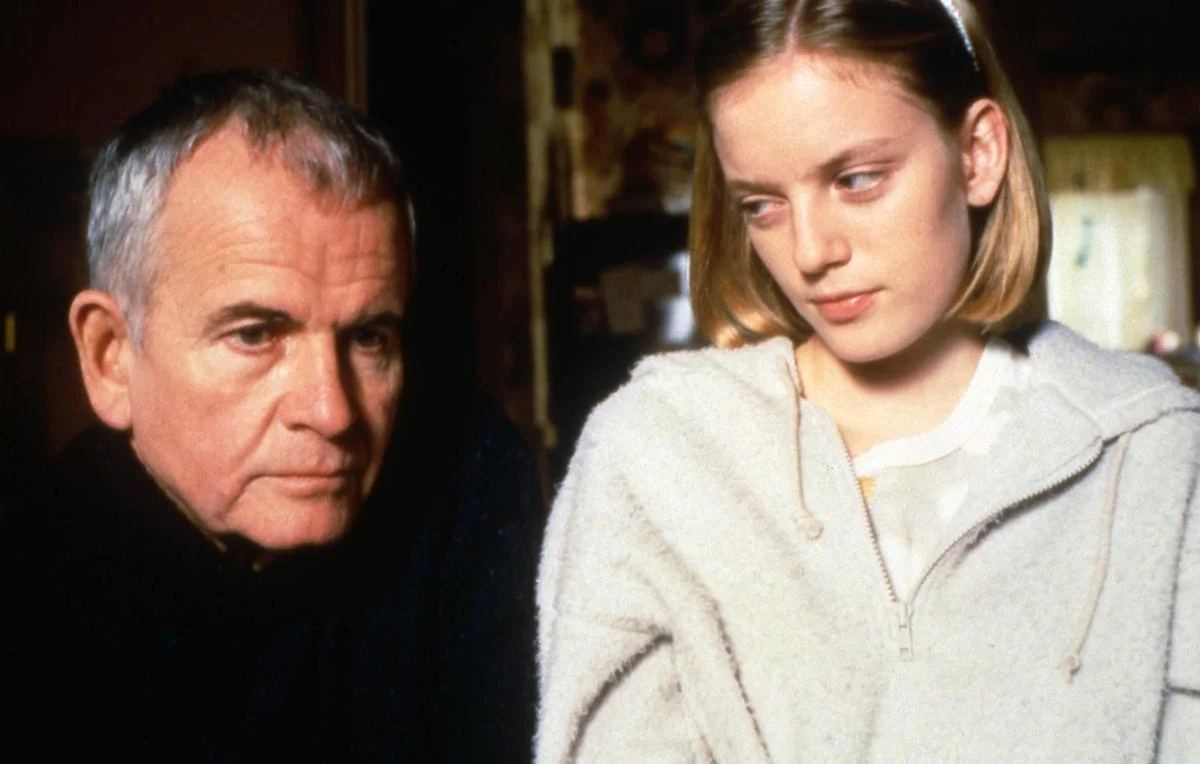

The Sweet Hereafter (1997)

Atom Egoyan received a Best Director and Best Adapted Screenplay nomination at the Academy Awards for this adaptation of Russell Banks’ celebrated novel, centered around the tragedy that befalls a small town and its inhabitants. Haunting in its central story, and in how it develops a compelling sense of misfortune and grief amongst its key central figures, it can be an especially difficult film to watch, let alone finish, a testament to the harsh qualities of its story.

Last Night (1998)

‘How would you spend the last day of your life?’ is the question that abounds this black comedy feature from director Don McKellar, that has become a favorite amongst many in the apocalyptic subgenre. A response to the Year 2000 hype and hysteria, the film follows various Toronto citizens who meet with friends and family for the last time, find themselves engaged in unexpected situations at the hands of others, and considering their past actions in the face of utter destruction. While grim at points, it does provide some moments of relief, and anticipation for what lies in the great beyond.

Emporte-moi (1999)

Lea Pool’s feature about the life of a young girl, Hanna (Karine Vanasse) living with her grandparents in a rural setting, who returns home to be with her mother and father after entering puberty. At the same time, she begins to see the realities of her parents personal situation, who are in their own ways depressed and hopeless. Hanna begins to become engaged through the world of film, gaining an attachment to Godard’s Vivre sa vie. It’s a sad, but sweet film, with a great performance by Karine Vanasse, and one which deserves to be more widely appreciated.

Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001)

The first film made in the Inuktitut language, Atanarjuat is a massive accomplishment which combines normal with the abnormal in a retelling of a famed Inuit myth. Visually, there’s nothing else like it, and the way Zacharias Kunuk frames the film’s sense of action (especially the thrilling chase sequence midway through) make it an essential production within the history of Canadian motion pictures.

C.R.A.Z.Y. (2005)

Jean-Marc Vallee is mostly known to American audiences for his recent features Dallas Buyers Club and Wild, but with C.R.A.Z.Y. he made a name for himself. It’s the story of a family and the one black sheep son, Zac (Marc-Andre Grondin) attempting to find his true sense of self and gain acceptance from his father. With awe-inspiring visuals and music choices, it’s far and away one of the most significant breakthroughs for a director and amongst Vallee’s best to date.

Bon Cop, Bad Cop (2006)

A good mainstream idea of a Canadian film, highlighted by the transnational approach and its success at the box-office (enough to greenlight a sequel arriving later this spring), Bon Cop, Bad Cop is the Great White North spin on a Michael Bay action film, as agents from opposite sides of the language division (Colm Feore, Patrick Huard) are paired up to solve a case directly involved with Canadian hockey players. I’ll attest that a lot of the jokes are too over-the-top in signifying a sense of connection to national culture, though it does provide a succinct illustration of contemporary Canadian culture on screen.

My Winnipeg (2007)

Guy Maddin weaves in fact and fiction in this partially autobiographical foray into his hometown life and past experiences, that verge on authenticity but are packed with ludicrous moments and imagery that make you question the authenticity of his stories. Perhaps Maddin’s best film, as it takes the avant-garde approach he finessed over several earlier films and rearranges it into a more palpable configuration, it’s also equal parts humorous and visually striking.

Incendies (2010)

Two siblings (Maxim Gaudette, Melissa Desormeaux-Poulin) travel to the Middle East to uncover the history behind their lineage, in Denis Villeneuve’s haunting look at the past lives we try to bury and the brutal truths that come to be unearthed. Villeneuve has taken on similar intense narratives with other films (such as 2009’s Polytechnique and the 2013 American-produced Prisoners), though Incendies provides for a unnerving shock once its dual narratives become intertwined, easily earning it a spot amongst his best.

Stories We Tell (2012)

Sarah Polley has featured in several notable Canadian films, though her later role as director has been equally as fascinating in the narrative features Away from Her and Take This Waltz. But her docudrama Stories We Tell, in which she uses the past anecdotes of her friends and family to speak about the life of her mother and the conflicting sides to which she is spoken about. A beautiful work which features a major revelation within, it stands to be one of the more interesting approaches to a documentary in some time, not just in Canada but worldwide.

Mommy (2014)

Xavier Dolan’s 1:1 frame feature is perhaps his most moving work to date, the story of a woman attempting to care and provide for her mentally unstable son, and the loving bond that carries through even in moments of utter turmoil and despair. The framing decision, akin to that of your average Instagram photo, helps to close in on the sense of desolation experienced between this bond, but makes for an aesthetic choice that results in being extremely powerful at the same time. While Dolan has made 6 features to date (with another on the way), Mommy remains an exciting, enthralling, tour-de-force of impressive fortitude.