A Beginner's Guide to Transcendental Style

Paul Schrader’s filmography and his ultimate influence in the art-house circuit is vastly greater than his collaborations with Martin Scorsese, although sculpting the electricity and enigmatic terror of Taxi Driver's Travis Bickle is enough of an achievement for any lifetime.

Originating in criticism and screenwriting before primarily working as an auteur of niche, oppressive, nocturnal projects – Paul Schrader can be mentioned with the Movie Brats like Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, but he’s largely on his own wavelength away from the populist cinema of the classical Hollywood era or that which found inspiration in morning serials. Instead, his book 'Transcendental Style in Film’, particularly within the works of Yasujiro Ozu and Robert Bresson, informs a lot of his tendencies and preoccupations, which are evident in the release of his latest film, First Reformed.

Transcendental style, as Schrader states, discusses “a common film style used by various filmmakers in divergent cultures to express the transcendent.” It is a constant “striving towards the ineffable and invisible” in spite of the art itself never reaching such a status. Schrader’s mystery, in his writing and directorial efforts, is determined to sort through this unknown, while never expecting to solve what is unsolvable. ‘Transcendental Style in Film’, then, is a book that sorts through the successes and personal traits of the exemplified films which acutely capture the yearning for transcendental feeling. Their differences are less important than their similarities, however, and Schrader soon digs into a universal, overpowering ability for these films to rise above their own (intentional) trappings of a “cold, unfeeling world” by simply introducing an “irrational and undefined” passion into a heartless existence. The ultimate catharsis of the work doesn’t come from the action but, as Schrader labels it, the “stasis” (the previous two are known as “everyday” and “disparity”), which is a re-configuration of the film’s hard, normalized style, only influenced by what has occurred.

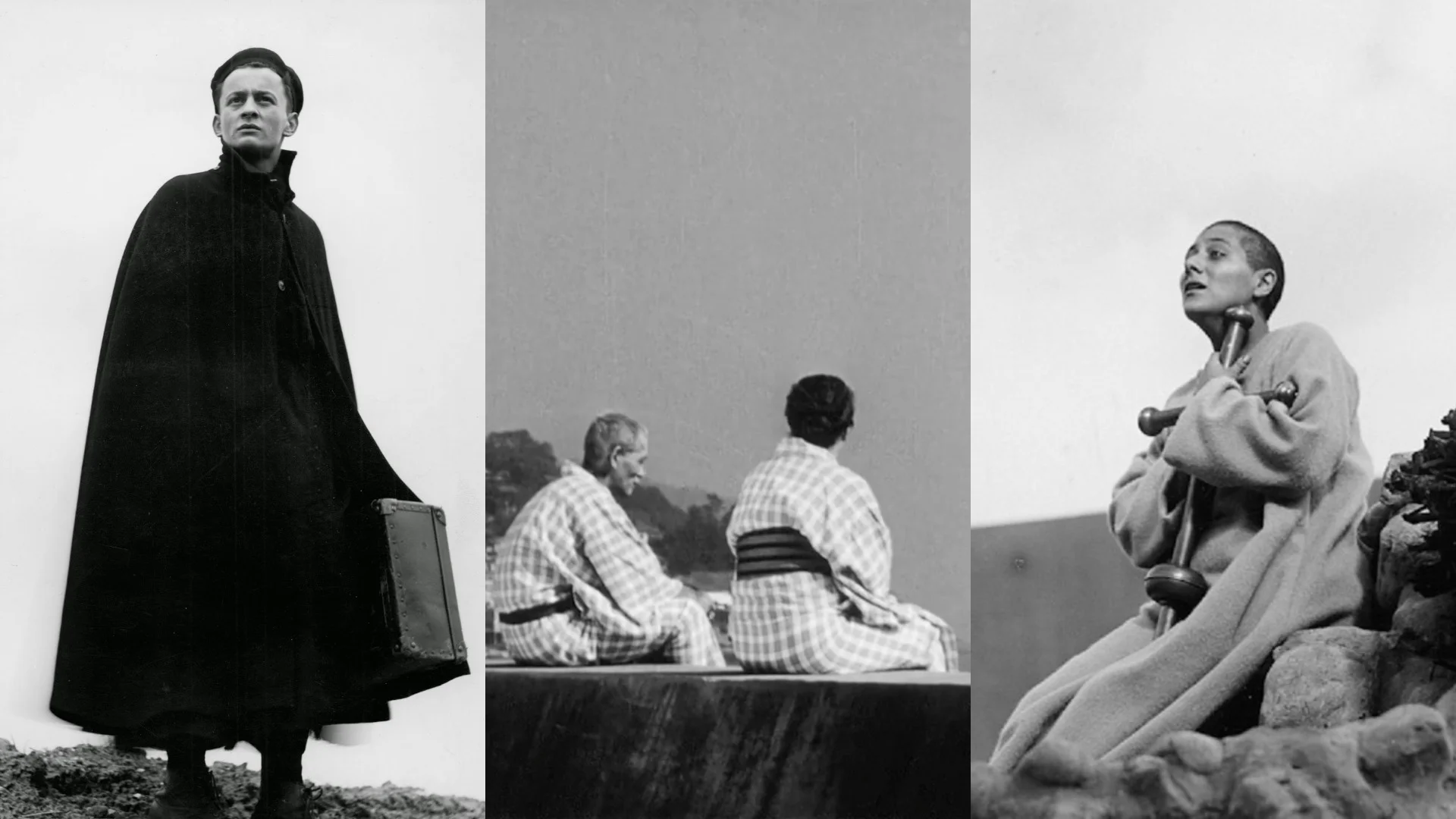

Paul Schrader’s book was revolutionary in the discussion of the differences between experience and expression, and how transcendental art began with the former and ended with the latter, rooting grand emotional responses in intellectual theory and understanding. The published work explored films such as Ozu's Tokyo Story, Bresson's Diary of a Country Priest, and Carl Theodor Dreyer's The Passion of Joan of Arc, with numerous references to other films. Previous critical theory is even more prominent in ‘Transcendental Style’, however, as Andre Bazin and Donald Richie provide an extensive framework of Schrader’s didactic expansions. If anything, this 1972 work is the New Hollywood of concepts infused throughout the 1950s and 60s period of academia and criticism. It doesn’t come as much of a surprise that Schrader himself was a protégé of Pauline Kael. But it is a surprise how, after reading, how this discussion lingers in the reader’s mind. Films such as Ordet and Day of Wrath continuously find new viewership through their applied status in regard to Schrader’s ruminations (although it helps that Dreyer is an established canon filmmaker of the 20th century), and those who veer towards a more popular art-house mode, like Ingmar Bergman, are invigorated by found elements of transcendental style.

In particular, Bergman’s 1963 film Winter Light, released shortly after 1961’s Through a Glass Darkly and before The Silence, is bracingly economical and influential, and a troubling, complex first step away from Dreyer and Bresson in their earlier careers. The IMDb synopsis, which simply reads “a small-town priest struggles with his faith”, is no comparison to the reality of its existentialism and pain of the unknown, which is never fully resolved. Bergman equates a transcendental style to the hardship, and revelation, of God's silence, which is a practically an ancient version of Schrader’s concept for First Reformed.

The body can only take so much, and the mind is frequently let down by what we do not know or cannot comprehend, but the fact that we can push through our Earthly pain by committing to Earthly duties, and in a sense, rise past the realities of the everyday, is Schrader’s ultimate breakthrough, both as a writer and an artist. The world still looks the same at the end of the day, and yet, the way you perceive the fabric of the known existence is fresh and anew.